“A Humble Bridge”

Representing Woody Guthrie in A Complete Unknown

“Ladies and Gentlemen …Woody Guthrie.”

The recently released film, A Complete Unknown, directed by James Mangold, sets out to tell the story of Bob Dylan’s early years in New York City. Billed as a Dylan biopic, the film works more as an essay on creative becoming as Dylan (played marvelously by Timothée Chalamet) emerges as a folksinger and songwriter before moving into more electric music following a divisive concert in 1965.

Speaking to Stephen Colbert, Chalamet described the film as “a humble bridge” to the music of Bob Dylan (and, by extension, the entire era). An evocative, giving phrase, Chalamet seems to take his role as a Dylan ambassador seriously. His entire press tour for the film has been a wondrous example of an inspired actor placing his work in the hands of as many people as possible. So much of the conversation in the world of Dylan studies has centered on whether the film will create new audiences for the music and work of the people in the film (and depending on where they exist on the gatekeeping spectrum, whether this is a good thing). It is a bit early to say if younger listeners will show up.

Dylan arrived in New York in January 1961, where the film starts, and infiltrated the various folk music establishments in Greenwich Village. Woody was on his mind, however, and numerous stories of their first meeting crashed into one another as myth and fiction took hold. Still, at some point, he goes out to the Guthrie home in Queens—which the film omits—before getting instructions on how to reach the hospital. Guthrie had been in Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital since 1956, where the film implies that Dylan first met Woody. In 1961, however, Woody was moved to Brooklyn State Hospital.

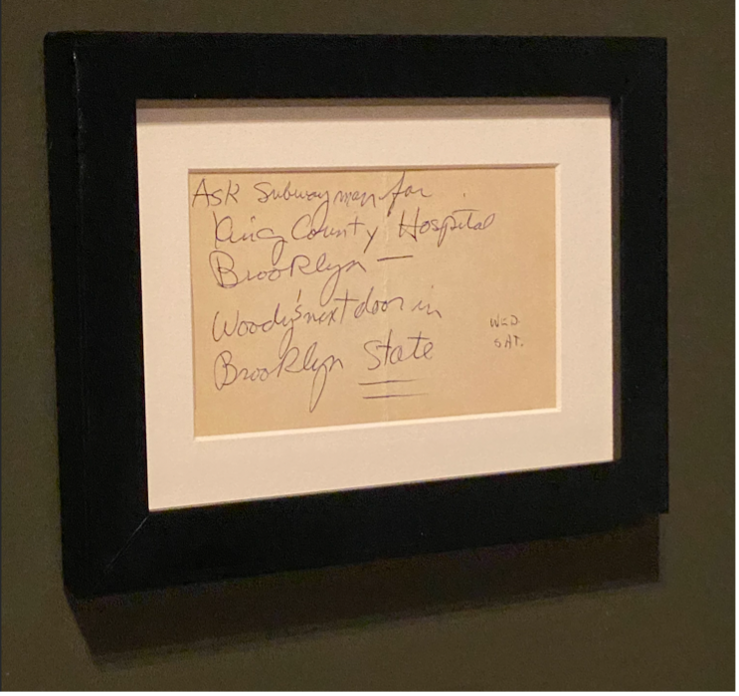

Despite the difficulty of placing this meeting in the realm of sources and facts, a bit of historical ephemera still exists: a card from Gerde’s Folk City, the West Village music club, with Dylan scrawling on the reverse the directions to Brooklyn State Hospital: “Ask subway man for King County Hospital Brooklyn.” “Woody’s next door,” he writes, “in Brooklyn State [underlined twice].” Off to the side he notes “Wed[.] Sun.,” most likely the hospital visiting days. A talismanic reminder that within the whirlwind of myth and memory, these connections and meetings were tangible and real.1

Despite the fact that, depending on whom you ask, the last fifteen or so years of Guthrie’s life were spent in the throes of Huntington’s disease, the single Woody biopic (Bound for Glory) stops well short of this period. Scenes in Alice’s Restaurant take place in Guthrie’s hospital room, but the Guthrie portrayed there is quiet, calm, and completely silent, more like a sick child in a Victorian novel. On the other hand, A Complete Unknown elevates that room so that it stands at the center of Dylan’s spiritual and artistic being. Despite the film seeming to endorse the common association of Dylan with endless movement and change, its story is also circular, starting and ending in that room—the kind of room that is the site of many, many people’s invisible domestic lives. The patient we find living in that room is clearly ill and disabled. Yet, the filmmakers put most of the struggle with Huntington’s—by this stage, would have been putting Guthrie’s body in continual, drastic, involuntary motion—in Woody’s facial muscles.

Scoot McNairy’s portrayal of the now permanently hospitalized Guthrie is thoughtfully poignant and expressive. Muted by the throes of the disease, Woody’s illness left him unable to play guitar or sing. McNairy telegraphs the frustration of the disease, especially as Seeger and Dylan drift in and out unbounded by the physical limitations suffered by Guthrie. The intensity of McNairy’s facial expressions and deliberate movements characterize Woody’s rebellious personality, and the initial meeting between him and Dylan does not rely on pity or lament but instead focuses on an exchange between the two songwriters: Woody’s curiosity and Dylan’s admiration. In this way, the scenes featuring Woody serve as a framing device for the film not only to chart Dylan’s arrival in New York but to signal to a younger generation of folk artists forging ahead on their own road—one built upon the legacy of what Woody, Seeger, and many others had created.

Reflecting on his early years for an interview in the Martin Scorsese film No Direction Home, Dylan noted, “I was born very far from where I’m supposed to be, and I’m on my way home, you know?” “I had no past really to speak of, nothing to go back to—nobody to lean on.” “I mean,” he continued, “I just don’t feel like I had a past.” These interviews emphasize Dylan’s uneasy relationship with his personal history. He changes his name, moves around, and concocts wild tales of living in an infinite series of places out west. In a connected way, the Dylan-Guthrie relationship represents a tight cluster of reverence, assimilation, tethering, and an existential distance. The teenaged Dylan seemed to understand the meaning embedded in Guthrie and his music—the ancient past drawn from the folk tradition but embodied in a tangible person still alive. His discovery of Woody Guthrie offered a new way of fastening himself to a persona to navigate his relationship to a past as well as to a historical narrative of leaving home and, by extension, redefining the concept of home. Thus, Dylan traveled to New York in a moment of rambling reverence, of mystic pilgrimage, to call on the man who opened up new paths.

On Valentine’s Day, 1961, just a month into his New York City life, Dylan gifted Sidsel and Robert Gleason—fans of Woody’s who had served as his caretakers when he was in Greystone—with the lyric manuscript of his first significant composition: “Song to Woody.” Dylan set the song’s melody to Guthrie’s “1913 Massacre” and built a compelling portrait of searching, leaving, and tipping his cap to those who came before. In a few verses, Dylan inserts himself into the folk tradition, pays tribute to his hero, fleshes out a new way of living, and waves goodbye from just a few steps ahead—an audacious start of finding and losing oneself in the same instant. In the film, Dylan tells Seeger that he “wanted to meet Woody—maybe catch a spark.” Chalamet’s Dylan then sings “Song to Woody” directly to McNairy’s Woody. “I’m out here a thousand miles from my home,” Dylan sings at the very beginning of his career, and in so doing, he worked to craft a map of escape through song. The songwriter from Okemah, Oklahoma, sits at the center of these plot lines, and to understand Dylan, one must ultimately confront the meaning and significance of Woody.

The Dylan-Guthrie relationship is only hinted at in a handful of scenes (the hospital room appears four times throughout). Once, Dylan plays “Blowin’ in the Wind” using Woody’s famous “This Machine Kills Fascists” guitar. Later, he gifts Woody a portable record player, which Seeger notes in a visit (with The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan on deck). In that scene, Woody motions for Pete to take a harmonica from his hand. Seeger soon realizes it is a gift for Dylan.

In an interview in July 2024, as the press surrounding A Complete Unknown grew, the director James Mangold discussed how he got Dylan on board for the movie. “The first time I sat down with him,” Mangold says, “Bob said, ‘What’s this movie about, Jim?’ I said, ‘It’s about a guy who’s choking to death in Minnesota, and leaves behind all his friends and family and reinvents himself in a brand new place, makes new friends, builds a new family, becomes phenomenally successful, starts to choke to death again — and runs away.”

Dylan’s response: “I like that.”2

Critics and academics will tirelessly break down the fictions, errors, and omissions in this film. While this may be a worthwhile endeavor, the movie nonetheless does something exceedingly well: it creates the emotional tableau where Dylan meets Woody and where that takes him. The film opens with Woody singing “Dusty Old Dust (So Long, been Good to Know You),” which appears again during the closing credits in a version featuring Chalamet. Part of his “Dust Bowl Ballad” cycle, this song reflects on Guthrie’s time in Texas (Pampa is in Gray County) as the apocalyptic dust storms threatened livelihoods and lives. But Guthrie also taps into the cosmic pragmatism of moving on, somehow, someway. “We talked of the end of the world,” Guthrie sings, “and then we’d sing a song an’ then sing it again.” Much of the story between Dylan and Guthrie exists within the irony of saying goodbye as you are saying hello. A calling card, “A Song to Woody,” also worked as a closing chapter. Dylan’s “I’m a-leaving tomorrow, but I could leave today,” echoing Guthrie’s “So long, it’s been good to know yuh.” It is time for something new, Dylan implies—time to lace up the worn-soled boots and head out for the ever-expanding road.

The film ends as it begins: with Dylan visiting Guthrie in the hospital. Post-Newport, with “Like a Rolling Stone” ascendant, Dylan returns to Guthrie’s hospital room. It is difficult to denote just when Dylan stopped visiting Guthrie. Their interaction carries the weight of myth, with most of the focus on that first interaction and the few times that followed. However, as Dylan moved away from Guthrie as a performer, he might have also closed the door to Woody in his private life. “I really cared,” Dylan tells Scorsese, “I really wanted to portray my gratitude in some kind of way.” “But,” he notes, “I knew that I was not gonna be going back to Greystone anymore.”

In the film’s final scene, Chalamet (channeling Cate Blanchett channeling Dylan) is couched in the windowsill playing harmonica along to the song that opens the movie: “Dusty Old Dust.” Thirty years old in 1965, this song helps frame the entire film’s discourse on folk music, the role of tradition in the face of cultural change, and the need for goodbyes. Dylan hands the harmonica back to Guthrie, who simply taps it with his fist and bestows it back to the young man on the cusp of one more drifter’s escape. The harmonica, a humble bridge of its own, connects the two men—a workaday folk object now permeated with the past and present of popular songwriting. Dylan removes his sunglasses and reaches out to caress Guthrie’s head. And then, in a portentous blur of motorcycle roar and gravel crunch, Dylan disappears down the road once more.

Recommended Reading:

Buehler, Phillip. Woody Guthrie’s Wardy Forty: Greystone Park State Hospital Revisited. Woody Guthrie Publications, 2013.

Carney, Court. “Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and the Implications of the Past: A Case Study.” In Erin C. Callahan and Court Carney, eds., The Politics and Power of Bob Dylan’s Live Performances: “Play a Song for Me,” (Routledge Press, 2023): 1-9.

Carney, Court. “‘With Electric Breath’: Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968),” Woody Guthrie Annual, Vol. 4 (2018): 22-39.

Stadler, Gustavus. Woody Guthrie: An Intimate Life. Beacon Press, 2020.

In April 1963, Dylan recited his poem “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie” at the Town Hall in New York City. Near the end, he states: “You can either go to the church of your choice / Or you can go to Brooklyn State Hospital / You’ll find God in the church of your choice / You’ll find Woody Guthrie in Brooklyn State Hospital.” Bob Dylan, "Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie," The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3, Columbia Records, 1991.

Brian Hiatt, “Inside ‘A Complete Unknown’: How Timothée Chalamet Became Bob Dylan,” Rolling Stone, July 24, 2024.